Product leaders need to pay as much attention to the revenue model as the product and customer. Pricing and packaging have become too intertwined with both the product and customer behavior to be ignored and left to other functions in the business. And while all the elements of your business model (see Osterwalder’s canvas) are important for innovation, I’ve found the revenue model — how you make money — to be of outsized importance.

The top VCs have long known this. While disruption is often built upon technical advances, it’s business model innovation that creates true strategic advantage and business returns. As USV’s Fred Wilson once said, “Everything changes when you change the business model; all of sudden, your strengths become your weaknesses.” (link, min 14:30)

Just think about how new entrants have flipped the tables on the incumbents: SaaS players, starting with Salesforce, turned software from something you bought to something you rented. Spotify did the same in music. And now, when you look at the games that top the app-store leaderboards, they’ve largely switched from charging to buy the game to selling virtual goods or virtual currency.

Don’t get me wrong: the revenue model isn’t the only place for innovation. With Uber, a rider still pays for a ride. Uber transformed the world by creating a marketplace, by taking advantage of advances in mobile and GPS technology to simplify the UX, and by using flex pricing to help solve supply and demand issues.

That said, if there is one thing I’ve learned, it’s that your revenue model significantly contributes to, or fights against, your ability to create a flywheel for your business. It directly creates or throttles customer behavior.

An example

A few years back, I ran product at a fintech marketplace called Axial. You can think of it as a marketplace for buying or investing in small to medium-sized companies. Buyer’s said, “Here’s the kind of business that we want to buy.” Sellers said, “Here’s the kind of business we are.” The matching engine connected the two sides, bringing efficiency and opportunity to an incredibly information-inefficient space largely driven by personal relationships.

When I joined, Axial mostly made their money by charging buyers a subscription fee to be on the platform. There were a few tiers to the subscription, but it was largely “all you can eat.”

Pros to the subscription model:

- very low friction to acquire sellers, which was the harder half of the market to get on board

- easy for buyers to understand

- a recurring revenue model (in theory)

- nice cash flow, given that a lot of customers paid for a year up front

Cons to the model:

- Created friction adding buyers to the platform

- Required an expensive sales force for the price point

- Enabled buyers to cast a very wide net

Let me explain that last one, because it was really important. If there’s one thing private equity investors like, it’s to get a look into lots of deals. They’ll say no to 99.9% of the deals they see, but they don’t want to miss the one they really want.

The subscription model let buyers set their interests very wide. When you listened to what they said in customer research, they thought this was a good thing. They got to see more deals! However, to the sellers, this was horrible. The list of recommended buyers was way too noisy — too many names and too many poor fits. Investment bankers were not impressed. This marketplace was supposed to create efficiency not noise!

Ironically, while buyers said they wanted to see more deals, they also kept on saying that the quality of deals on the platform was low. The problem wasn’t quality, because quality is in the eye of the beholder. Case in point: some investors hate distressed businesses and some love them. Seeing more deals wasn’t their true goal. Closing good deals was their true goal. As an aside, this is a classic example of how qualitative research must dig deeper than surface-level answers to true, underlying motivations.

The company decided to run an experiment. What if we lowered the subscription cost to nothing or near-nothing, and charged buyers for each lead? No surprise: buyers immediately tightened their matching criteria. There was no feature, no UX change, that was going to change human behavior as well or as quickly as making a revenue model change.

The story doesn’t actually end there. The per-lead model wasn’t a panacea. It had it’s own strengths and weaknesses. Axial has found even better results by charging a success fee on transactions that actually close (which happens to be a model that buyers in the space are already familiar with). Now Axial is directly aligned with the true goal of their customers, which should also make it easier for the product team to prioritize the right things.

What are examples of revenue models?

- One-time purchases – you buy and get the thing (up-front or in installments)

- Rental / subscriptions – you all know about this — much of the business world has moved to this model as it delivers recurring, more predictable revenue. However, much as investors tend to love this model, don’t just blindly assume that it is best for your business.

- Advertising – an old model that has been particularly effective in consumer tech. As we’ve seen with the social media giants, it can create really low friction and thus user growth. It can lead to misaligned incentives and bad side effects (looking at you Facebook).

- Pay per use / pay per transaction — whether fees for usage tiers, or transaction commissions, this has long been a great revenue model for marketplaces, as it aligns the business with increasing transaction activity. Variations of consumption-based pricing are becoming more popular as it reduces friction to initial purchase (think: land and expand)

- Lead gen / affiliate fees — related to the above, and also very effective for marketplaces, but explicitly about charging for customer lead generation.

- Tipping / donations — where customers have the option of donating a certain amount to the company. In certain domains, this has proven even more effective than directly charging, but the most successful variations appear to be in domains tied to a good cause and where there is already a monetary transaction happening that you can piggyback on top of.

- Maintenance fees / add-on services — some companies treat maintenance or add-on services as upsell revenue streams, but you can design a model where the product itself is free, or near-free, and you make your money from maintenance, support, or services. A classic example is open source companies.

- Crypto tokens — this is an area that is very new and rapidly evolving. It has the potential to align the interests of all parties in a product ecosystem, but is still confusing to a lot of people. Still, if you are looking for a way to disrupt your field with revenue model innovation, you should absolutely look at this. I hope to write more on the topic later.

As an aside, I consider things like discounts or “freemium” to be incentive variations on the above models, as opposed to models unto themselves.

5 Questions to ask

If you are putting your design hat on around your revenue model, I have 5 questions I like to ask.

1. Can we make enough money given our cost structure?

This is just business basics, and requires getting into a spreadsheet and examining your assumptions carefully. Will these lead to a business with attractive margins.

2. What makes it easy to buy?

Complex pricing models — or too many options — are a good way to get potential customers to bounce. Don’t make it too confusing or too hard for someone to buy from you. So you need to understand how your competitors, especially the incumbents, charge for their product/service. That doesn’t mean you have to copy them — the answer might be that you should reduce friction by going along with how everyone else charges, or the answer might be that you want to disrupt the field by changing the model. The last part of this is making sure you understand how your target customers purchase. Do they have procurement or budget processes or rules?

3. What are the customer behaviors we want to encourage vs throttle?

Given the above example, hopefully this question now makes sense.

4. What gives us an advantage & turns our competitors strengths into their weaknesses?

Should you and can you innovate here? Do the hard, creative work here to really examine this question.

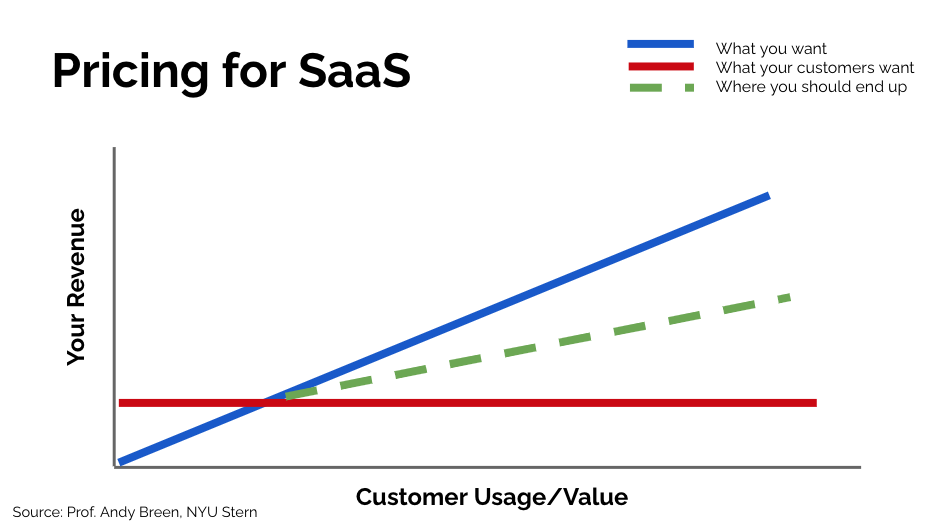

5. How do we align incentives so that we make more money as our customers are more successful?

Often customers want to pay a flat fee, with the notion that as your product delivers more value, they get to keep that value and increase their ROI. But this is actually not in their interests and certainly not in yours. First of all, it’s a lot easier to grow revenue from existing customers than by acquiring new ones, so you must have this ability built into your model or you’ll have a mediocre business.

But it’s in your customers’ interests to have you aggressively investing in improving the product and delivering more and more value. If you are too greedy, they will resent the attempt to take too much of the ROI of your product and they will leave you for an alternative. If they are too greedy, they’ll actually be leaving future value on the table because you won’t have an incentive to invest and deliver it to them. I can tell you from experience, as CPO of a company that suffered from the malaise of not being able to make more more from successful customers, having misalignment on your revenue model makes in damn, damn hard to prioritize the right things from a product perspective.

There’s a nice slide from my fellow professor at NYU Stern, Andy Breen, in our Technical Product Management class that illuminates this nicely:

How can you put these ideas into practice?

- Think of your revenue model as part of the system of your product and visualize (draw!) how it connects to your incentive system. Is it helping to build a flywheel for your business or is it stifling your flywheel?

- Diverge and converge: whether on your own or with some colleagues, explore the various revenue models that exist and play out how they could apply to your business. Run them through the gauntlet of the above 5 questions. Many won’t fit your context, but explore the full problem space anyway.

- Take the most interesting ideas into a spreadsheet. This is the only way to truly expose your assumptions.

- Design and run experiments. Unless you are an early-stage startup, my recommendation is to be transparent with the market about why you are running these experiments. At Meetup, we stumbled into a PR nightmare when a tiny experiment went viral and the world thought that we were making a major policy change — all because the company hadn’t gotten ahead of this (the reasons are too messy to go into). You also have to be careful of both early false positives and negatives. Experimentation is a must but don’t expect early validation.

- If you’re an established company, go very carefully. You might decide to “grandfather” in some of your install base, but don’t hand this out too easily or necessarily make permanent. A revenue model change can feel, and be, quite risky, but then again, it can also deliver amazing upside if designed well and rolled out well (communication, timing, cohorts, etc).

- Learn but have conviction. Customers hate change. You might get early blowback, but if you truly believe in it, don’t be too reactive. Sometimes it takes time for customers to understand the why, but if your new model truly aligns everyone (as opposed to merely being a way to make more money from them), they will come around.

If you’re interested in learning more on this topic, there is the book Monetizing Innovation, by Madhavan Ramanujam and Georg Tacke. Within the subscription space, you should also pay attention to Patrick Campbell at ProfitWell. If you are interested in usage/consumption-based pricing, Kyle Poyar at Open View Venture Partners has been putting out great material.

Questions or comments? Hit me up on Twitter.

Top image by Bill Oxford on Unsplash