Andrew Chen, long one of the best startup/growth voices out there, just tweeted about “The Traction Treadmill” —“It’ll kill your company,” he writes. Before I go on, let me explain what he means by that term. You’ve got a startup with okay customer retention, but not great. You successfully boost growth by doubling or tripling sales & marketing spend. You’re still churning users but at small numbers, you stay ahead of this and continue to grow. It’s only once you expand into larger numbers (thousands, tens of thousands), your churn acts as an anchor. Now you’re spending tons of money and energy only to run in place. Growth hacking provides temporary solutions that prove ephemeral. And here’s the rub. As Andrew writes, “The problem with the treadmill is that your team and scale makes it hard to iterate substantially on the product and business. You’re locked in.” You’re bigger, you’ve got more engineering resources, but you’ve also got a lot more code and design complexity baked into your product. Capital dries up, morale plummets, and it’s game over.

The challenge for entrepreneurs is that Andrew’s good advice contradicts much of what they see and hear.

“Do things that don’t scale”

“Growth takes care of the rest”

“Get yourself the funding and thus the runway to fix your problems”

“Fake it till you make it.”

Also confusing the waters: founders see other startups out there who have raised a lot of money while patching over churn problems through customer success, hype, and VC-fueled momentum. These distortions are made worse by how attention works in startupland — we talk/hear about the companies when they appear to be doing well, but once they stumble they turn invisible.

Case in point: I was once with a company that grew nicely right through their series-C by diversifying into new customer sector after customer sector, until they ran out of new sectors. Then their churn problems ate them alive and there was no more VC lifeline to keep the wheels turning. I can attest to the fact that it’s brutal fixing these problems at 100, 200, 300 people rather than at 20.

Another trouble for founders is that too few investors, outside of the pre-seed set, really care about product. These mid-to-later stage investors care about growth and are obsessed with distribution (sales and marketing). You can understand why — they’re expecting their money to be used to scale. That’s what they were pitched to win their money. Those pesky product and business model problems were supposed to be solved in the earlier stage. The company has product-market fit, right?! Unfortunately, too often those problems are, indeed, patched over. When the truth becomes impossible to avoid, tensions at the top become even uglier because of the mismatch of investor expectations and the realities of the company.

The Problem with “Product-Market Fit”

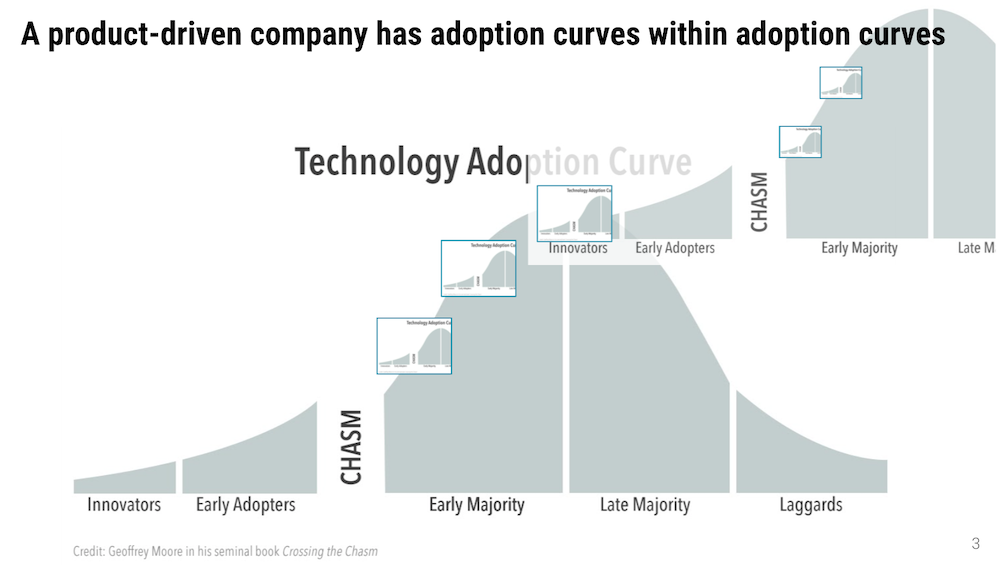

The phrase product-market fit is used everywhere, at companies large and small. Most people treat it like a line in the sand: we are pre-PMF or post-PMF. That’s not really how things work. Target markets are really made up of many niche customer segments. The adoption curve for companies is really made up of many smaller adoption curves. I try to teach aspiring product managers that every new feature, let alone new product, has an adoption curve.

When founders think of product market fit as a “pre and post” concept, they have to convince themselves that they are post, or very near post. If they can’t convince themselves, how can they ever convince investors to give them money? The answer is: they can’t. So all the incentives and pressure in the system points to papering over the issues and getting that growth.

It doesn’t matter how good Andrew’s advice is when most people fall prey to the incentives of the system.

Sean Ellis’ Universally Ignored Advice

The very best advice about startup growth that I’ve ever read comes from one of the fathers of growth hacking, Sean Ellis (also the man who created the useful “very disappointed” survey). Sean argued that startups should first make sure that the product (and I’ll add, revenue model) is working. Customers are seeing value. Retention is looking good and sustainable. At this point (and earlier) most startups want to pour on the gas, but Sean says hold on! Now take several months and fix your top-of-funnel. You’ve probably got a very leaky bucket. Improve those conversion rates and optimize that first user experience (phase 2). Once that is done, now pour on the gas (phase 3).

Almost no one does this. People skip over phase 2, or to Andrew’s point, even skip over phase 1. There is simply too much pressure in the VC ecosystem to grow. There is seemingly plenty of evidence that growth begets growth but again there’s a catch. VCs really only need, and expect, 2 in 20 startups to succeed. They have a portfolio. You, as founder or exec, have a single shot. You’re committed. But what is prudent usually falls prey to growth pressure in startupland. Investors protest and say comments like this are unfair. “We’re not telling our CEOs what to do!” But I think it’s exactly the incentives of the VC system that fuels this.

So what to do?

If you are lucky enough to be one of those companies that is seeing phenomenal growth and retention, don’t change a thing. Keep on rocking out — keeping up with that kind of growth is a challenge unto itself. But that’s a single-digit percentage of startups. My advice for the others, equally as hard to follow as Andrew’s advice, is to use restraint.

If your business hasn’t yet clicked into a truly working system, don’t try to scale. Note that I didn’t say don’t ship, I said don’t yet try to scale. Focus on product value, revenue model, and enough of a repeatable customer acquisition process that your business becomes economically sustainable or at least your runway is bearable. Learn aggressively outside of your walls (virtual or otherwise). Pay more attention to your revenue model than your thought you needed to — is it helping or hurting your flywheel? In many cases, you’ll also need to narrow your target customer segments, while keeping an eye on the bigger market. Do not raise venture capital money to solve your traction/retention problem. Don’t even try, because all that energy will take away from what you really need to solve.

Throughout this phase, you need to remind yourself that the Traction Treadmill is a mirage — trading short terms wins for medium term pain. Avoid the temptation of hail mary plays that might land you that next batch of funding and buy you the time to solve these problems — that’s also a high-risk mirage.

Don’t get me wrong. I know people who have pulled this off, but it’s going all-in on a pair of fives.

I’m keenly aware that my advice is an absolute bitch to follow, because it requires money and therein lies the nasty, horrible, catch-22 of startups. It’s why I swore to myself after my last startup that I wasn’t founding another unless I had saved up 2 years of personal runway — the ability to go for a full 2 years before needing to raise capital. Which is, of course, exceedingly difficult to do. Impossible for many if not most. Certainly impossible for me right now with a family.

So we end up right where we began. Founders think, “I’m already taking on risk, so what’s a little more. Go for the growth, sell that vision, raise the capital, and then pull that rabbit out of the hat. Andrew’s right, but I can’t afford his advice. Others have done it, why can’t I? Hell, look at so-and-so. They’re famous now!”

It’s alluring. But the trade often leads to more pain down the road. Early stage comes with pain, but deeper pain comes later when you have employees and investors and customers counting on you, and your business starts to stumble. When the reality of fake-it-till-you-make-it starts to come home to roost. The layoffs begin and you can see the feelings of betrayal in your employees’ eyes. You harden your mind and heart just to survive to emotions of it all, but that’s just a delaying tactic. The toll will hit sooner or later. And you have to suffer the realization that you have invested so many years of life, sacrificed so much due to excessively long hours, just to get a shot at reaching the sun, only to have it snatched away.

Young founders don’t want to hear this stuff. “That won’t be me,” they think. “Our idea is hot, our team is great, we’re going to be one of the ones that make it.” It doesn’t matter how many people preach a more restrained approach. More and more of us veterans are saying, “Only go-big-or-go-home startups should raise venture capital. The majority should not.” New founders don’t want to hear it. Often, they can’t because, honestly, they need the capital. Their option isn’t what kind of startup should I do, but rather, can I do a startup at all?

But the truth is that Andrew is right. Sean Ellis is right. So the question to most founders is this: are you able to buck the incentives, resist the screwed up nature of startup mythology and optics, and do the smart thing?

By the way, Andrew Chen has a new book coming out that you can be sure I’m going to read: The Cold Start Problem.