This post roughly mirrors a talk I gave about a month ago to two product manager communities (Product School and Product Faculty). If you prefer watching video, a recording of one of the talks is here.

Roadmaps are an important and necessary part of the product manager job. They allow us to refine our own thoughts, set expectations inside (and often outside) of our companies, and build alignment. That said, there are also land mines to avoid.

When I joined Meetup as CPO, the newly-installed CEO had just completed a strategy document that laid out big, outsized goals. At the time, all things WeWork had outsized goals! The strategy doc was clear on vision and targets, but it didn’t include a path how to get there. That’s where a roadmap was needed, and it was my job, with the help of a great team, to create it.

During the creation of that roadmap, I’ll freely admit that I made a few avoidable mistakes that came from one root cause: I didn’t ask all the right questions. Even worse, these were questions that I *knew* I should ask but which I still neglected in the heat of moment.

I’ve come to believe that good product management is so context-specific, the most important thing for any PM is to make sure they ask the right questions. Put another way, while you can and should try out best-practices, a sophisticated PM doesn’t blindly copy other people’s answers.

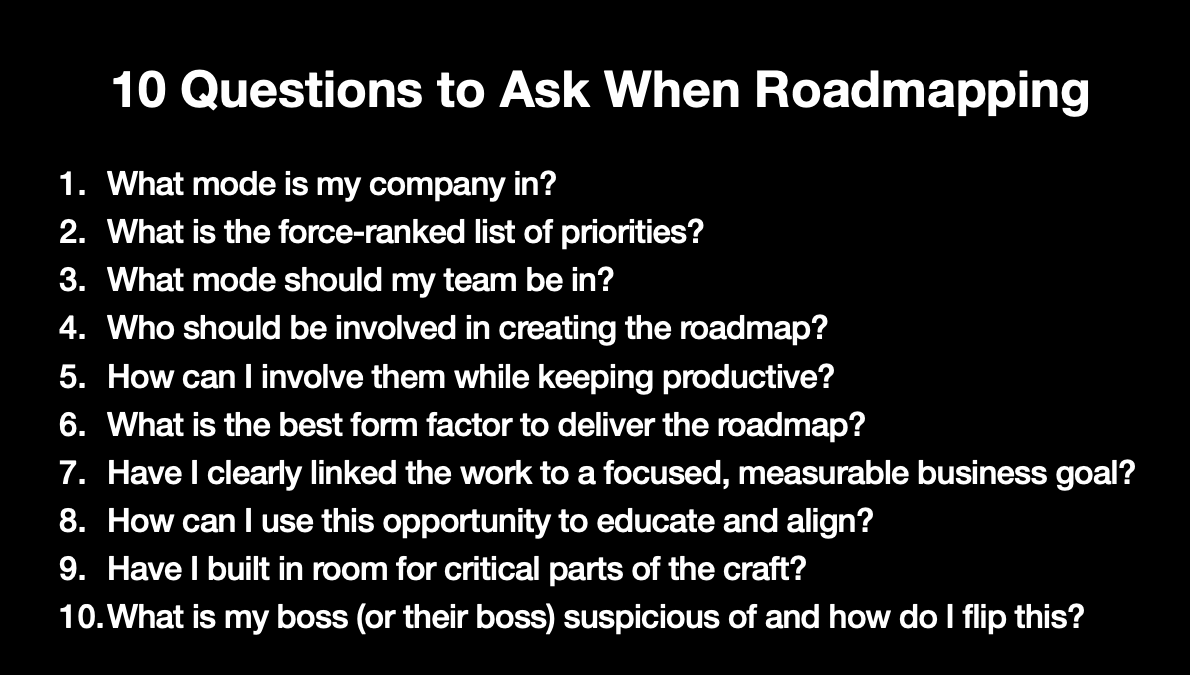

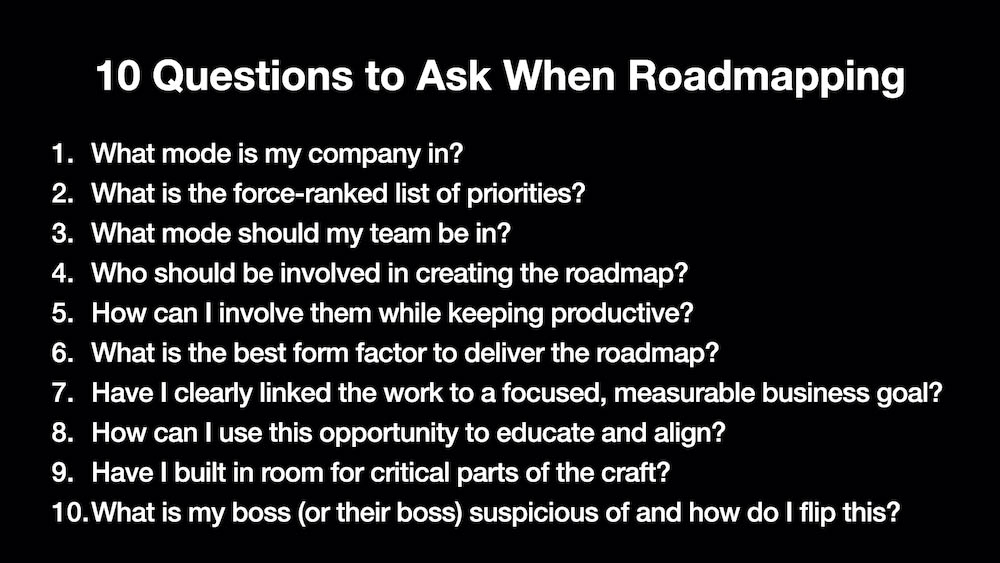

In this post, I wanted to highlight 10 important questions you should ask in your roadmap effort, and I’ve intentionally tried to reach beyond the typical customer- and strategy-centric questions to ones that are more at risk of being forgotten in the heat of the moment.

We’ll start with alignment, shift into communication, touch upon craft, and end on a more career-focused note.

1. What mode is my company in?

At any point in time, a company is in a certain mode, or gear, of activity. There are 5 big ones:

- scaling fast / high growth mode

- trying to unlock stalled growth

- defending against external threats (whether specific companies or other disruptions in the market)

- in need of transformation / reinvention

- maintaining cash flows (and avoiding the risks that comes with chasing growth)

The downstream implications of your answer are huge. It’s essential that you know which mode your CEO (and board) think the company is in. Misalignment will get you into trouble, because you’ll risk prioritizing and pushing for the wrong things.

It’s pretty clear when you’re in mode #1, but it be confusing to know which of #2, #3 and #4 you’re in. Leadership can mistakenly interpret the data coming in. It’s even harder for board members who are one step removed and who get a very filtered view. Ultimately, you can have healthy debate, but you’re going to need to disagree and commit to the CEO’s stance if you want to preserve their trust in empowered teams.

Last note: the mode you’re in can affect the amount of risk your team(s) can and should take on. Shooting for bigger impact sometimes means taking on more risk. That’s worth discussing explicitly as well.

2. What is the force-ranked order of your various goals and priorities?

At Meetup, we had a product team trying to improve the customer experience around email and push notifications. Put simply, Meetup was sending out too many messages. The team had two goals: (a) improve the customer experience without hurting key metrics by sending fewer but smarter notifs (the words in italics being the most difficult part of the whole effort), and (b) pay down tech debt on old, brittle infrastructure. The CEO wanted a third: (c) grow engagement metrics.

The team tried to take a portfolio approach, working across all three. It proved too much. They were spread so thin that progress felt slow on everything. The team needed to say no (or really, “not yet”) to more things, but making these calls by themselves in isolation would have been foolish. The solution was to pull the team, the CEO, and myself into a room to build consensus around what to truly prioritize.

Suggested exercise:

Write your many priorities down on index cards, one per card. Put them all on a surface, get the right group of people together, and then force the group to stack-rank them. Do not allow two cards to sit side by side.

When possible, I like doing this exercise in person with physical paper because it tends to better engage non-product/engineering types. But if your team is distributed, you can do this exercise with tools like Mural.co or stickies.io.

3. What mode should my team be in?

Just as a company has a gear, a team does as well. There are three typical modes of a team:

- hitting an “impact” goal

- discovering a path forward

- delivering a specific feature (often by a specific date)

The first is a common mode for a product team. For example, improve conversion rates by 20%. Or, lower total cost of ownership by 10%.

The second is all about innovation: you have to carve out new territory (a new market segment, revenue stream, etc) and you probably have more questions/assumptions than answers/facts.

The third is a mode PMs often resent, but there can be valid reasons why this is necessary: a promise to a big customer, or a need to tie a product release to an immovable marketing event.

You need to ensure alignment between you, your team, your boss, and executive leadership on this question. If you think you’re in #2 and an executive thinks you’re in #3, you’re in for a world of hurt. If your engineering leader thinks you’re in #1 and you think you’re in #2, you’ll be arguing all the time. Do not assume that your team knows which mode you are in, or why.

The way you execute will be different across these three. For the first, you’ll be running some experiments, but because you need to move that number, you need to be shipping. So broad brush, let’s say it’s 70-80% delivery and 20-30% testing. However, if you’re in the second, it’s a classic mistake to focus too much on product. You need to focus on learning, so qualitative research and experiments are the name of the game. Lastly if you’re in mode 3, you don’t want to be distracted by experiments — you need to be entirely focused on minimizing scope creep and delivery execution.

There can be some confusion between #1 and #2. If you really don’t know how to hit your impact goal in mode #1, then you’re really in #2. Just make everyone knows and aligns.

4. Who should be involved in creating the roadmap?

As a product manager, you might be a steward of the product, but you are the caretaker of something everyone cares about, and of which everyone has an opinion. As you are creating your roadmap, you need to be intentional about who is involved. Who on your team? Within the prod-eng-design organization? Across the rest of the organization? This can include people outside of your company (and for certain, external research should be fueling your hypotheses), but for this section, I’m particularly focused on people inside your company. Benefits to running an inclusive process include: a better roadmap (from the debate of ideas), reduced politics (by letting people be heard), and better odds of hitting your goals (because the company will be more aligned).

I made a mistake at Meetup doing that first roadmap. When I got there, the company had no roadmap. The teams were all working on useful but smaller optimizations. In the meantime, we had these huge goals! The discrepancy needed to be solved and quickly. I partnered up with Farah Assir, our VP of Design, who knew the product and customer cold. We took over a corner of one floor and started working in public on the walls.

I would grab a person from different teams (customer support, marketing, data science, etc) and pull them into our corner to discuss and debate our ideas. In my mind, I was getting representation from the different groups. In reality, I was offending people who were not chosen. I had inadvertently trip over a cultural sensitivity. Right or wrong, people felt that some previous executives had played favorites, creating an “in” and “out” crowd. They were suspicious that I was repeating that behavior. There I was, trying to be inclusive, but I still hadn’t thought deeply enough in my new context about who should be involved and why.

5. How can I involve them while keeping productive?

Of course, while you might want to be inclusive, you also need to move things forward efficiently, so this means intentionally designing how you involve people. Don’t just wing this — you’re a product designer right? So design this too.

Some tips here: if you want to get an honest back and forth with a very senior executive, meet 1-on-1. Executives have to be careful about what they say and how they appear in group settings, but 1-on-1 they can let down their guard.

If you want to include a broader team, consider running a “listening roadshow”. You know that prioritization exercise with index cards shared above? Try it with other teams within your company. Explain your possible priorities and ideas and then sit back and see how they would stack-rank the cards. Make sure you listen carefully — the discussion and debate is worth far more than the actual stack-ranking you get back. Don’t waste time defending your opinions and ideas. You’re there to listen. Make sure the team feels respected and heard. That will go a long way, even if they don’t get their wish list.

6. What is the best form factor to deliver the roadmap?

Your answer to this question will vary depending on your stage in your roadmap effort, the time frames you are aiming for, and your company culture.

Early on, you might be trying things like the above roadshow meetings, where you are presenting things as in-progress and you are listening more than talking. As things advance, you need to think above the various form factors for delivery.

There will probably be a document of some kind — is this long-form? slides? a video? a comic strip or storyboard?

There might be a presentation of some kind — who should deliver it? How do you paint an effective picture of both what and why?

At Meetup, our CEO preferred written documents to slides. The first version was very driven by Farah and myself, but we left the details loose so that the teams could come up with specific solutions. After the first big reset was complete, the PMs and their teams took over their respective sections and we kept one central, living document that was updated at least once a quarter.

When we getting close to a final draft of the first roadmap, we cloned copies for each team. We wanted feedback but desperately wanted to avoid the groupthink (and mess) that would occur with hundreds of people redlining/commenting a single document. So we gave each department a separate copy to attack.

When we released the final version across the company, we turned off comments, but at the end of every section there was a link to a Google form that allowed for questions and feedback.

When it comes to a live presentation, think about how to balance clarity and efficiency of delivery with inclusivity amongst your team.

7. Have I clearly linked the work to a focused, measurable business goal?

Let’s be honest: there are plenty of CEOs out there who think PMs and designers spend too much time thinking about customer delight and not enough time on what it means for the business. True or not, it is imperative to connect ideas and effort to impact, not just to the customer but also the business.

This can be very difficult. I have often worked on things that took multiple steps to achieve true impact. In other words, we had to do X in order to do Y which would then bring Z — and it was Z that would deliver meaningful lift to whatever number we cared about (customer ROI, revenue, profit, market share, etc).

It can be hard to justify X when it doesn’t have a direct ROI on its own. It can be hard to come up with hard numbers when Y and Z are in the future and you are guessing so much. It can feel like an exercise in bullshitting. Regardless, you need to connect those dots and do your best to forecast the future.

What if you’re scared to put forward a number and then be held accountable to a wild guess? The simplest answer is this: put forth a range, not a number.

8. How can I use this opportunity to educate and align?

If your company is like many, quite a few people haven’t used the product or spoken to a customer in a long time. Sometimes never! Even people in sales or customer support, who talk to prospects or customers all day long, have very context-specific sources of information.

A roadmap is a tremendous opportunity to ground your colleagues in who your customer is and what they are trying to solve, as well as what it will do for your company.

When product people are talking to each other, we often speak in shorthand around this stuff. One can assume knowledge. One can assume that the other person can connect the dots. It’s understood that we wouldn’t be talking about doing something if there wasn’t value attached to it.

You can’t make this assumption with the rest of the business. You need to be explicit about *why* you are proposing to do something. Not only will this help you achieve better alignment around your goals, but by refreshing your colleagues on customer value, you can often help them do their jobs better too.

9. Have I built in room for critical parts of the craft?

I couldn’t have a list of roadmap questions without asking this one. Have you made room for:

- quality and usability testing

- paying down technical debt

- internationalization

- instrumentation (and where applicable, variant testing)

- time to run necessary research & experiments

- effective release planning+execution

- iterating after the release

These are items that all too often get neglected in the rush to get something out the door and move on to the next “most important thing”. It’s particularly bad in cultures that set big goals but never properly evaluate how they do against those goals.

It can be ok to sprint to a release, making compromises along the way. We’ve all had to do it. But you want to build time for this list into your roadmap. You want to make these items as non-negotiable as possible, which being realistic/practical about necessary compromises. Bake them in. They are how we do our work.

Neglecting the above items leads to poor quality (higher customer churn), poor morale (higher employee churn), and increasing brittleness and friction in everything related to product and engineering (lower agility and velocity).

10. What is my boss (or their boss) suspicious of and how do I flip this?

View this question as an opportunity rather than a reason to get defensive. A good manager is always trying to understand the strengths and weaknesses of their employees, both to figure out where to help them grow, as well as to know how much “weight” to put on them (stretching without breaking).

Because a roadmap covers so many aspects of a PMs job (strategic, product and financial thinking; prioritization; internal and external communication; building alignment; setting expectations, and more), they are great opportunities to both grow and to show what you are capable of.

One question is: what are your weaknesses? Another is: what are your perceived weaknesses? And then how can you use the roadmap process to get help, strengthen some weaker muscles, and show your stuff?

I needlessly tripped over myself on this question during that first big Meetup roadmap effort. I had just been hired by the new CEO and we had never worked together. I knew what the CEO had been hiring for, but I hadn’t specifically dug into what the CEO was trying to avoid — what he was allergic to.

At the start of the roadmap process, I asked the CEO: do you like getting things early and raw, or later and more polished? He said early and raw. Great, I thought, since I’m a rough-draft-culture person. The sooner you can uncover misalignment the better! At the earliest stage, we were sketching out some big areas of investment, and I wanted him to understand the broad-strokes direction we were going. I sent over what could best be described as a loosely filled-in outline. He puked all over it. “Where was revenue?! How was this connected to revenue?!” Afterwards, he apologized and we laughed over some of his rougher comments, but I had failed both this question and question #7 above. In my mind, *everything* was attached to revenue, but the CEO wasn’t a product person and this was non-obvious. I knew better, but I still tripped up.

I learned that he had been burned in past by product leaders who weren’t financially-savvy or financially-motivated enough. He wanted someone who really bridged product and business. Of course he was looking to see if I would pass muster.

It all worked out fine. He learned I did care about both. And I don’t regret sharing the document early, but I needed to have connected the dots better before doing so, even if very loosely. One could also argue that I should have shared the early ideas in person, but I’ve also found benefit in letting people read and absorb quietly before a meeting. In any case, if I had thought a little bit more about what the CEO was paranoid about, I would have avoided the faux pas.

So there you go. There are, of course, many more questions that one asks in creating a roadmap. Since we product people have a tendency to get caught up in the strategy and features side of things, I hope this list has been a useful reminder.

p.s. I’m gradually working on a new book called First Principles Product Management. It’s a workbook of questions one should make sure to ask. I want to battle test the ideas in public. I’m building up to a first something to share, but if you’re interested being part as it evolves, let me know here. And feel free to comment on this post on twitter.

p.p.s. are you fascinated by where artificial intelligence is going? check out my science fiction novel Becoming Monday! Wait, what? Giff does fiction? No, seriously, people are really liking the book! It’s a fun ride and I hope you give it a shot.

Thanks to Unsplash for the images